Williams Jones sticks a magnet to a mix tank pump motor, then bends down and points a strobe light at the machine. He’s collecting data to make sure the machine is working properly.

Jones is a PdM lubrication technician and second-class mechanic at the Owens Corning roofing plant in Denver. His job is to monitor the equipment, do preventative maintenance and fix machine parts.

Jones really likes his job.

“Every single day it’s something new and that’s amazing to me,” he said. “I get to learn a lot of stuff.”

Jones tried a semester of college after graduating from high school, but it wasn’t for him. Four years ago, he started at Owens Corning in an entry-level position before switching to maintenance.

“All my education has been through this company, honestly,” said Jones. “They’ve provided me with a lot of courses to help develop me, which is why I like it and that’s why I’m still here.”

Jones is part of a certified two-year industrial mechanic apprenticeship program at Owens Corning. The program was created last July because the company was having a hard time filling critical skilled positions.

“What we have found is that there are less people that tend to pursue manufacturing as a career option,” said Jim Hill, the plant site leader. “We have to turn inside to fill those positions.”

The curriculum ranges from reading materials to shadowing more seasoned mechanics to hands-on-training. Its designed to get employees like Jones to a journeyman level.

Joe Garcia is the chancellor of the Colorado Community College System, the state’s largest system of higher education which educates over 137,000 students around the state every year. Garcia, who has spent most of his professional career in education, said it’s important to understand that a postsecondary credential doesn’t always equal a bachelor’s degree.

“Only about half of the jobs really require a bachelor’s degree,” said Garcia, who’s spent most of his professional career in education. “Many others require an associate’s degree or even a certificate. And if you talk to employers, they say their biggest challenge is really finding those middle-skilled workers.”

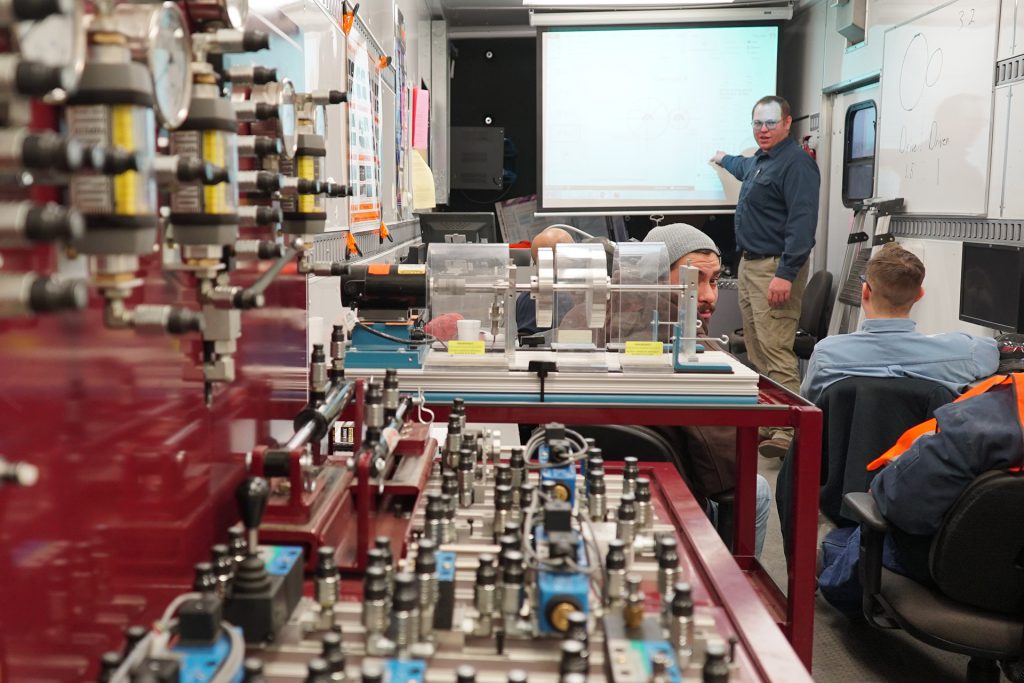

As part of the apprenticeship program, Jones is taking a course on mechanical systems. But instead of going to a community college, the classroom is in a 48-foot trailer parked right outside the plant.

The Mobile Learning Lab was created by the Pueblo Corporate College at Pueblo Community college. The corporate college specializes in providing educational opportunities to non-degree seeking students.

“We have replicated what a student would see if they’re on a campus taking classes in any of our technical training labs,” said Amanda Corum, executive director of the Pueblo Corporate College. “We have all that hands-on training equipment inside of an enclosed trailer.”

The first mobile learning lab was built in 2007. There are now seven that travel all over the state and have also provided training in Utah and New Mexico. The labs provide courses in electrical systems, mechanical systems, toolroom CNC milling and welding.

Jim Hill is the site leader at the Owens Corning roofing plant in Denver. (Stephanie Daniel/KUNC)

The Owens Corning roofing plant in Denver. (Stephanie Daniel/KUNC)

The labs were built for two reasons, said Corum. First, there was a capacity issue on campus. Enrollment in these classes was up so there wasn’t enough room for employees to be trained. Second, employers wanted a flexible training solution that could come to them.

“(Employers) have those travel costs that they’re reducing. They have access to their employees while they’re in training,” said Corum. “So should an emergency arise, they can tap into those employees that are right there.”

Lack Of Skilled Workers

In an apprentice program, a person is an employee first and a student second. Companies create these programs to enhance the skills of their workers. This could be either standout employees that want to move up or new hires with potential, said Lee McMains, chair of the industrial technology and energy studies at Aims Community College.

“Really start to not only teach them the culture of the company but also the skills that are needed in the company,” he said. “So, that they can provide more value as they move forward up through the corporate and career ladder.

The largest sector the Mobile Learning Labs serve is manufacturing, but they are also used to train employees that work in energy, oil and gas and mining, according to Corum.

“There is a cliff that’s coming and maintenance and automation technicians, they’re getting ready to retire.”

— Lee McMains, Aims Community College

In 2016, there were about 150,000 manufacturing jobs in Colorado, ranking it ninth for total estimated jobs by industry. These were high-paying jobs which paid, on average, $65,000 a year, according to state data.

A lack of skilled workers has been an issue in the manufacturing industry for more than a decade, said McMains. High school graduates who wanted to work with their hands were encouraged to pursue a four-year engineering degree, rather than a two-year technical one, which led to a lack of skilled technicians coming out of college, continued McMains.

“Now there is a cliff that’s coming and maintenance and automation technicians, they’re getting ready to retire,” he said. “There’s nobody coming behind them because everybody’s been told that they need to be an engineer and an engineer is just not going to work with their hands the way a technician would.”

Investing In People

The state is helping adults complete a postsecondary degree by investing in affordable and innovation options like the Mobile Learning Labs. Companies pay for the training and customize the curriculum to their needs, then the classroom comes right to the job site. It’s a win-win for the employer and employee.

“We need to invest in our people, so in the long term the plant can be sustainable,” said Peter Tobin, the maintenance leader at the Owens Corning plant. “I think it’s really shown a mutual investment from Owens Corning and from our employees to reach a goal.”

Jones recently finished a course in hydraulics that was also taught in the Mobile Learning Lab. While in this class, he went back to the plant during a break. Jones walked by a piece of equipment and heard a problem similar to one they’d just discussed in the lab.

“I was able to correct that issue right away and it was thanks to that course,” said Jones. “That’s the biggest benefit for me, is I’m learning stuff that I can do right now and I get to do it in there and out here. It’s awesome.”

Hire Me: Educating Colorado’s Changing Workforce was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.