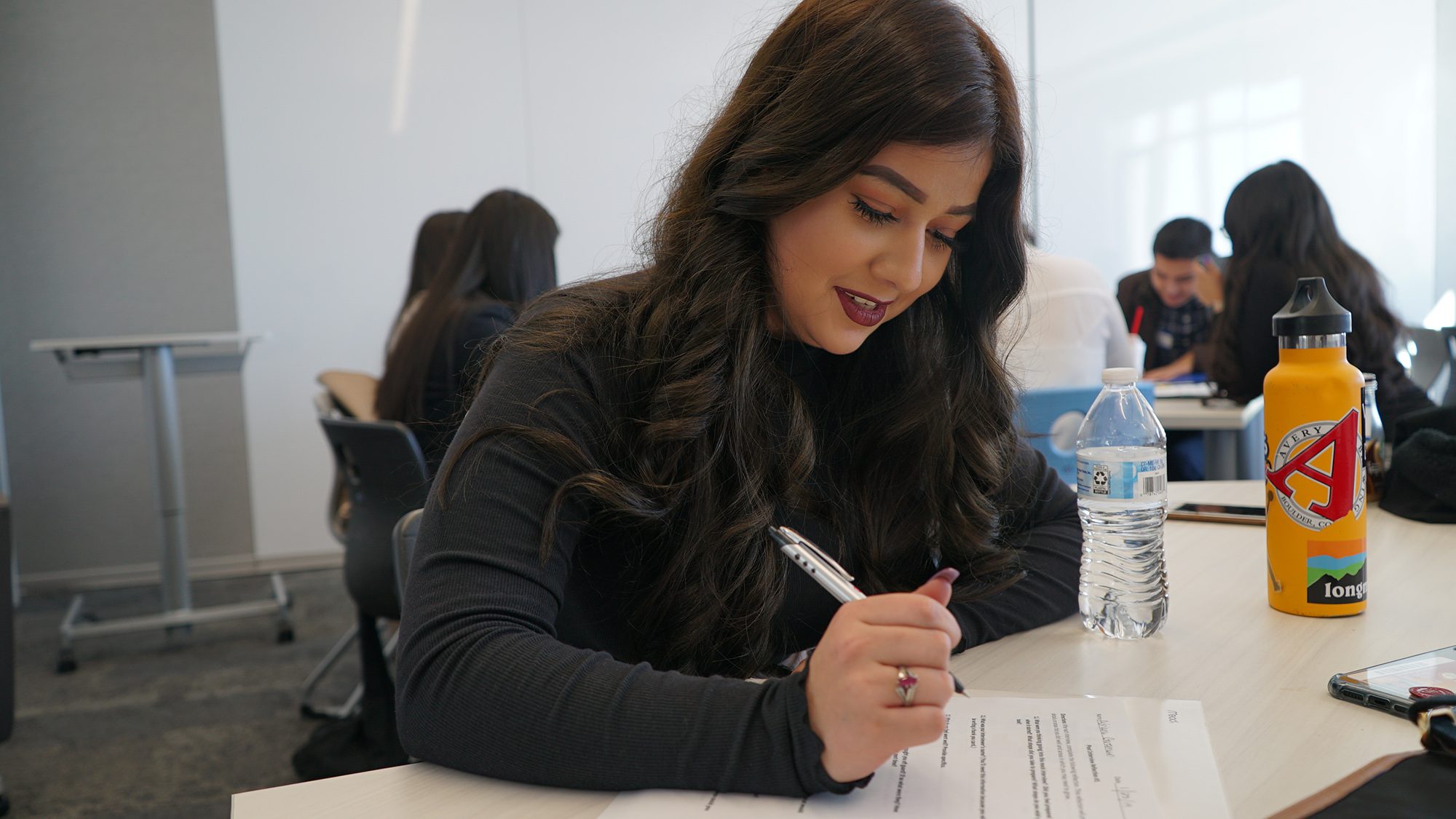

Jenny Sanchez is a first-generation college student.

“My mom stopped at sixth grade and my dad stopped freshman year of high school and they didn’t continue from there,” she said.

The 19-year-old is a freshman at the University of Northern Colorado (UNC), studying biology and pre-med. She wants to be a pediatrician one day.

“So, they’re like, ‘Do what we couldn’t do. And like be a better person,’” Jenny continued.

In the fall of 2018, 10,232 undergrad students attended UNC. Of those, 38 percent were first-generation students.

“I would say right now our greatest efforts need to be focused on retention. I’m not satisfied with our graduation and retention rates at this university,” said Andrew Feinstein, president of UNC. “We retain about 70 percent of our students from their freshman to sophomore year and we should be much higher than that.”

The Center for Human Enrichment (CHE) is an academic support program at UNC that works with first-generation students through a federally funded TRIO program. TRIO includes programs that assist and serve students from disadvantaged backgrounds, from middle school through college, in their pursuit of a degree.

Sanchez was part of another TRIO program in high school. So, when she decided to attend UNC, Sanchez applied to CHE and was accepted.

“The CHE program is actually the best place in my opinion,” Sanchez said. “I love it here.”

CHE serves 200 students and provides an array of services including advisors, academic support and financial aid assistance. The staff, most of whom also identify as first-generation students, regularly meet with CHE participants.

“I think it helps when we are able to tell students, ‘I get it. I had that same experience when I was in school,’” said Shawanna Kimbrough-Hayward, director of CHE. “Knowing that there’s someone walking alongside them helps them to do well and to graduate.

In 2018 CHE students had a higher six-year graduation rate, 65 percent, than total undergraduate students, 47 percent, at UNC.

Another component of CHE is the peer mentoring program.

“It’s a cool opportunity for a first-generation student to have another first-generation student to just talk about life,” Kimbrough-Hayward said.

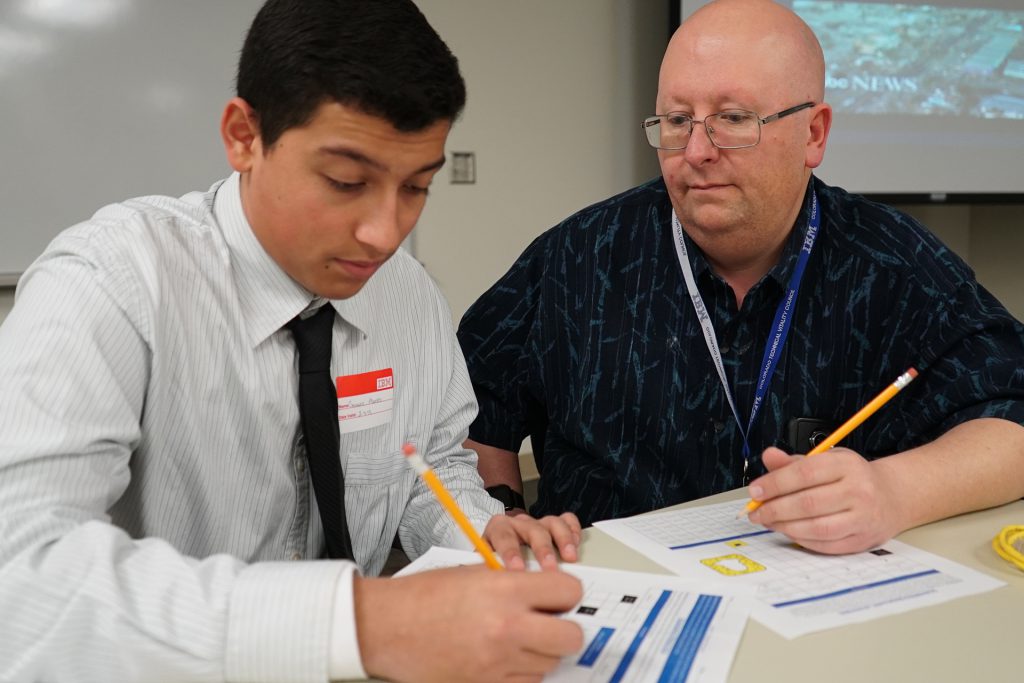

Sanchez’s mentor is 19-year-old sophomore Lizbeth Cortez-Contreras, who is pursuing a double major in pre-nursing and nutrition with a minor in Spanish. Sanchez and Cortez-Contreras were paired together in part because of their academic interests and because they are both female LatinX students.

“As a peer mentor, I was to give Jenny the sources and support I didn’t have my freshman year,” Cortez-Contreras said.

Cortez-Contreras went to a high school in the Denver metro area where the class sizes were small and most of her classmates were people of color. When she took introductory biology her first semester of freshman year, Cortez-Contreras said it was a shock. There were about 200 students in the lecture course and most of them were white.

“So being the only brown person there, it was kind of like outcasting to me,” Cortez-Contreras said. “I felt like kind of like the ugly duckling.”

Changing How Faculty Teach

In 2017, UNC received a $1 million, five-year grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The goal of the grant is to help students of color – like Cortez-Contreras and Sanchez – who are studying science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) succeed.

“The grant really focuses on increasing the diversity of students entering the programs but also looking at equitable outcomes,” said Susan Keenan, a professor and director of the School of Biological Sciences.

Keenan heads up the Howard Hughes Medical Institute grant which focuses on faculty change. The goal is to help faculty understand the student population and create environments within and outside their classrooms that enable each student to feel like they belong.

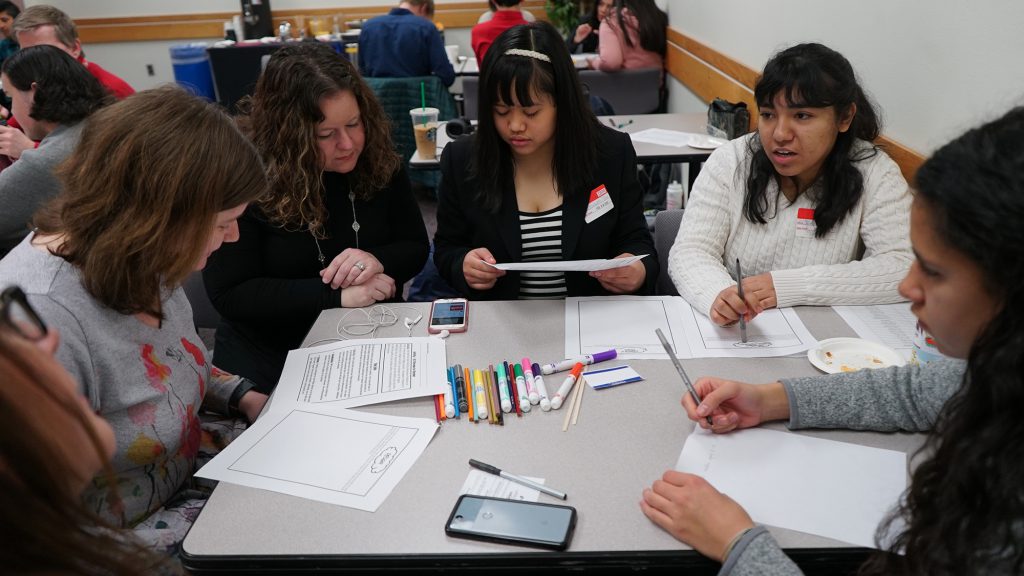

The grant was received in September 2017 and 10 faculty members from across the STEM disciplines are part of the program. They participated in summer workshops and have monthly sessions during the school year. Here the faculty discuss different topics like the structure of the syllabus or encouraging female students and students of color to participate in class. Then action steps are given which the faculty can choose to incorporate while teaching.

“They go into the classroom and try and then they reflect on what they’ve learned and what’s working and what’s not working,” Keenan said. “When we come back together everyone has had an experience. They share that and then we kind of all learn collectively from what people are doing.”

There are about 80 faculty members in STEM at UNC. The overall goal of program is for 50 percent of the faculty to go through the training. Keenan hopes that will be a big enough group that change will occur. She said taking responsibility, as an institution, for students’ success is the right way to go.

“I think that having faculty learn and understand the experiences of the students on campus is incredibly important,” Keenan said. “Creating an environment where everyone feels like they can achieve and they can thrive here.”

Paying It Forward

Cortez-Contreras is finishing up her sophomore year at UNC. She works as a front desk assistant in the CHE office, is part of the club tennis team and hopes to study abroad in Peru or Colombia soon. Cortez-Contreras said she feels confident now.

“I feel like I got the whole college thing,” she said. “So, I know what to expect and like I know what’s next, what’s ahead of me.”

Sanchez is also feeling more confident as her first year in college ends. During high school, she was part of a college readiness program and is now paying it forward, tutoring middle and high school students in the same or similar programs. Sanchez said it was a great experience for her to have college students as tutors. They made her feel more comfortable and prepared going into UNC.

“I just told myself, ‘You know what? I want to help those other students because there could be students that are terrified to come to college,’” Sanchez said. “I just want to be there like, ‘You know what? It’s not that scary.’”

Hire Me: Educating Colorado’s Changing Workforce was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.